Daniela Cossio

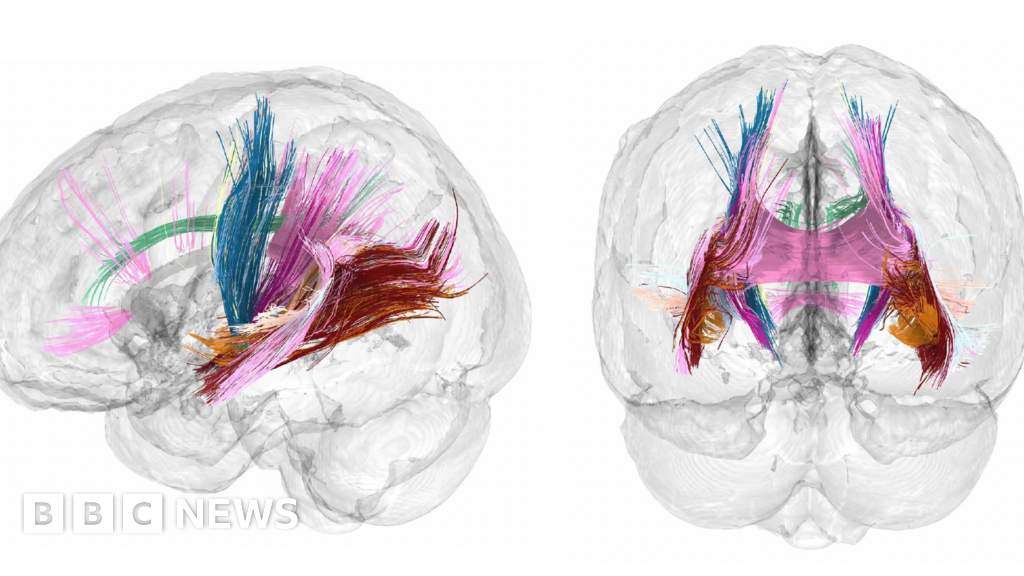

Daniela CossioPregnancy brain really does exist, according to one of the first detailed maps of human-brain changes before, during and after those crucial nine months.

Based on 26 scans of one healthy 38-year-old woman’s brain, scientists found “remarkable things” including changes to regions linked to socialising and emotional processing – some of which were still obvious two years after giving birth.

Further studies in many more women are now needed to determine the potential impact of these brain changes, they say

And those insights could improve understanding of the earliest signs of conditions such as postnatal depression and pre-eclampsia.

“It’s the first detailed map of the human brain across gestation,” Emily Jacobs, study author and neuroscientist, from the University of California, Santa Barbara, says.

“We’ve never witnessed the brain in a process of metamorphosis like this.

“We are finally able to observe changes to the brain in real time.”

Elizabeth Chrastil

Elizabeth ChrastilThe massive physical changes to the body during pregnancy are well known but much less is understood about how and why the brain changes.

Many women talk about having “pregnancy brain” or “baby brain”, to describe feeling forgetful, absent-minded or having brain fog.

Previous studies have focused on brain scans before and soon after pregnancy, rather than throughout.

The brain studied in the research, published in Nature Neuroscience, is that of scientist Elizabeth Chrastil, from University of California, Irvine’s Center for the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory.

She was planning an IVF (in-vitro fertilisation) pregnancy when the research was being discussed and now has a four-year-old son.

It is “cool” to study her own brain in detail and compare it with those of women who were not pregnant, Dr Chrastil says.

“It certainly is a little strange to see your own brain changing like this – but I also know that to start this line of research needed a neuroscientist to do it,” she says.

Laura Pritschet

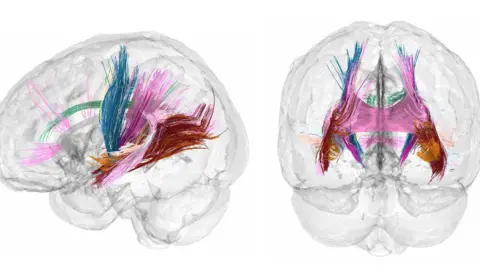

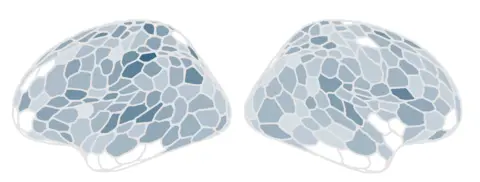

Laura PritschetIn nearly 80% of the regions of Dr Chrastil’s brain, the volume of grey matter – tissue that controls movement, emotions and memory – decreased by about 4%, with only a small rebound after pregnancy.

But there were increases in white-matter integrity – a measure of the health and quality of connections between brain regions – in the first and second trimesters, which returned to normal levels soon after birth.

The changes are similar to those during puberty, the researchers say.

Studies in rodents suggest they could make mothers-to-be more sensitive to smells and prone to grooming and nesting, or homemaking.

“But humans are way more complicated,” Dr Chrastil says.

She did not personally experience any “mommy brain” during her pregnancy but was certainly more tired and emotional in the third trimester, she says.

The next step is to collect detailed brain images from 10 to 20 women and data from a much larger sample at particular timepoints, to capture a wide range of different experiences.

In this way, Dr Chrastil says, “we can determine whether any of these changes could help predict things like postpartum depression or understand how something like pre-eclampsia could affect the brain”.