Getty Images

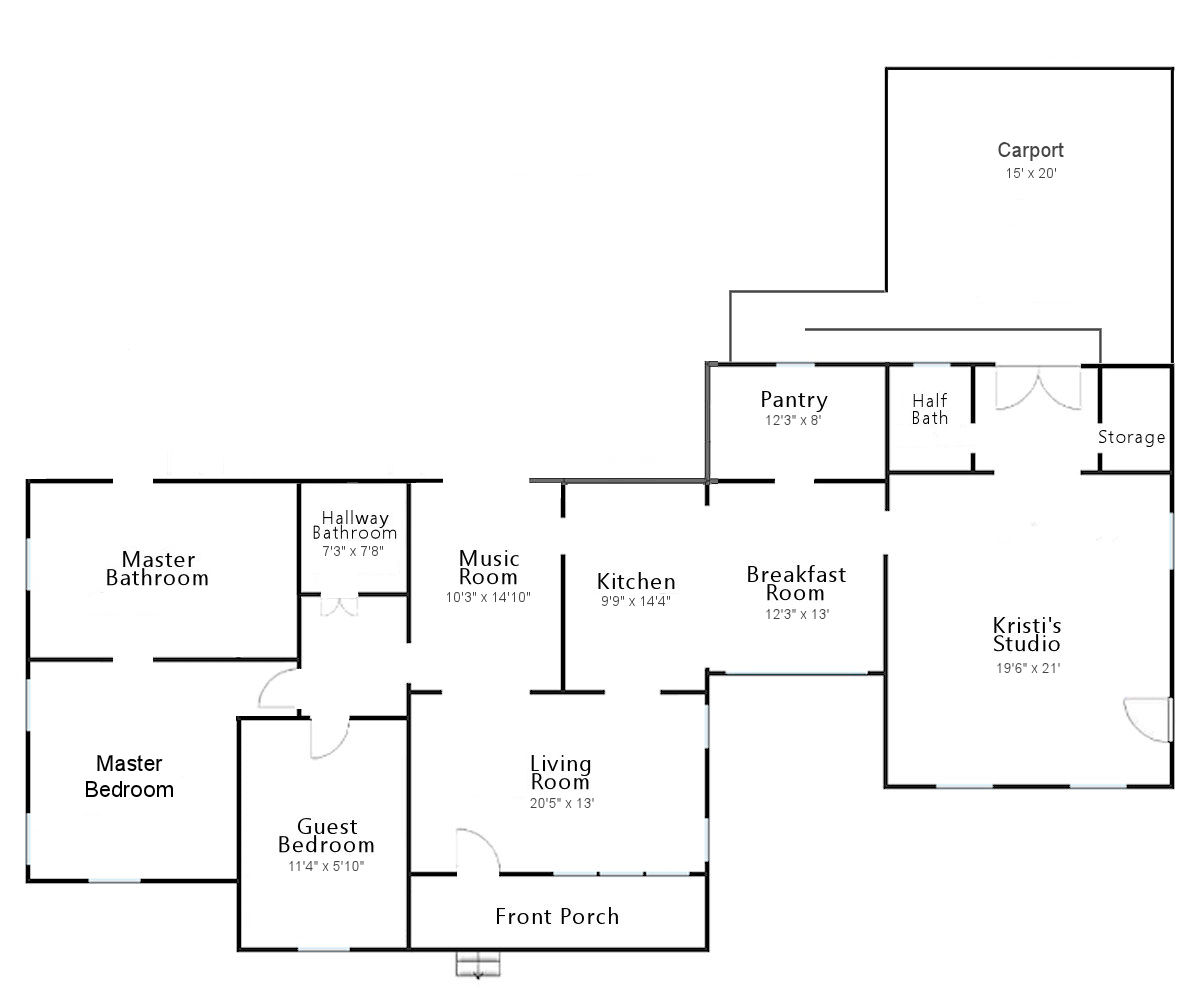

Getty ImagesA team of scientists say it is “beyond reasonable doubt” the Covid pandemic started with infected animals sold at a market, rather than a laboratory leak.

They were analysing hundreds of samples collected from Wuhan, China, in January 2020.

The results identify a shortlist of animals – including racoon dogs, civets and bamboo rats – as potential sources of the pandemic.

Despite even highlighting one market stall as a hotspot of both animals and coronavirus, the study cannot provide definitive proof.

The samples were collected by Chinese officials in the early stages of Covid and are one of the most scientifically valuable sources of information on the origins of the pandemic.

An early link with the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market was established when patients appeared in hospitals in Wuhan with a mystery pneumonia.

The market was closed and teams swabbed locations including stalls, the inside of animal cages and equipment used to strip fur and feathers from slaughtered animals.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTheir analysis was published last year and the raw data made available to other scientists. Now a team in the US and France says they have performed even more advanced genetic analyses to peer deeper into Covid’s early days.

It involved analysing millions of short fragments of genetic code – both DNA and RNA – to establish what animals and viruses were in the market in January 2020.

“We are seeing the DNA and RNA ghosts of these animals in the environmental samples, and some are in stalls where [the Covid virus] was found too,” says Prof Florence Débarre, of the French National Centre for Scientific Research.

The results, published in the journal Cell, highlight a series of findings that come together to make their case.

It shows Covid virus and susceptible animals were detected in the same location, with some individual swabs collecting both animal and coronavirus genetic code. This is not evenly distributed across the market and points to very specific hotspots.

“We find a very consistent story in terms of this pointing – even at the level of a single stall – to the market as being the very likely origin of this particular pandemic,” says Prof Kristian Andersen, from the Scripps Institute in the US.

However, being in the same place at the same time is not proof any animals were infected.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe animal which came up most frequently in the samples was the common raccoon dog. This has been shown to both catch and transmit Covid in experiments.

Other animals identified as a potential source of the pandemic were the masked palm civet, which was also associated with the Sars outbreak in 2003, as well as hoary bamboo rats and Malayan porcupines. The experiments have not been done to see if they can spread the virus.

The depth of the genetic analysis was able to identify the specific types of raccoon dogs being sold. They were those more commonly found in the wild in South China rather than those farmed for their fur. This gives scientists clues about where to look next.

Reading the virus’s code

The research teams also analysed the genetic code of the viral samples found in the market, and compared them to samples from patients in the early days of the pandemic. Looking at the variety of different mutations in the viral samples also provides clues.

The samples suggest, but do not prove, that Covid started more than once in the market with potentially two spillover events from animals to humans. The researchers say this supports the idea of the market as the origin, rather than the pandemic starting elsewhere with the market adding fuel to the fire in a superspreading event.

The scientists also used the mutations to build the virus’s family tree and peer into its past.

“If we estimate when do we believe most likely the pandemic started versus when do we believe most likely the outbreak at the market started, these two overlap, they’re one and the same,” says Prof Andersen.

In their scientific publication, the full genetic diversity of coronavirus seen in the early days of the pandemic was found at the market.

Prof Michael Worobey, of the University of Arizona, said: “Rather than being one small branch on this big bushy evolutionary tree, the market sequences are across all the branches of the tree, in a way that is consistent with the genetic diversity actually beginning at the market.”

He said this study, combined with other data – such as early cases and hospitalisations being linked to the market – all pointed to an animal origin of Covid.

Prof Worobey said: “It’s far beyond reasonable doubt that that this is how it happened”, and that other explanations for the data required “really quite fanciful absurd scenarios”.

“I think there’s been a lack of appreciation even up until now about how strong the evidence is.”

Did the pandemic start here?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe lab-leak theory argues that instead of the virus spilling over from wildlife, it instead came from the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), which has long studied coronaviruses.

It is located a 40-minute drive away from the market. The US intelligence community was asked to weigh up the likelihood of a leak – either accidental or deliberate.

In June 2023, all the agencies involved said either a leak or animal origins were plausible scenarios.

The National Intelligence Council and four other agencies said animals were the likely source. The FBI and the Department of Energy thought it was more likely to be a laboratory incident.

Prof Andersen said: “To many this seems like the most likely scenario – ‘the lab is right there, of course it was the lab, are you stupid?’. I totally get that argument.”

However, he says there is now plenty of data that “really points to the market as the true early epicentre” and “even locations within that market”.

Identifying the animals that could have been the source of the pandemic does provide clues to where scientists could look for further evidence of an animal origin.

However, because farms destroyed their animals in the early days of Covid it means there may no longer be any evidence left to find.

“In all likelihood, we missed our chance,” says Prof Worobey.

Prof Alice Hughes, from the University of Hong Kong, who was not involved in the analysis, said it was a “good study”.

“[But] without swabs from the actual animals in the market, which were not collected, we cannot obtain any higher certainty.”

Prof James Wood, the co-director of Cambridge Infectious Diseases, said the study provided “very strong evidence” of the pandemic starting in wildlife stalls at the market. However, he said it could not be definitive because the samples were collected after the market closed, and the pandemic probably started weeks earlier.

And he warned “little or nothing” was being done to limit the live trade in wildlife, and “uncontrolled transmission of animal infections poses a major risk of future pandemics”.