A rare eruption of light from a dead star will likely be visible to people on Earth this summer in a fleeting but potentially stark celestial display that scientists are calling “a once-in-a-lifetime event.”

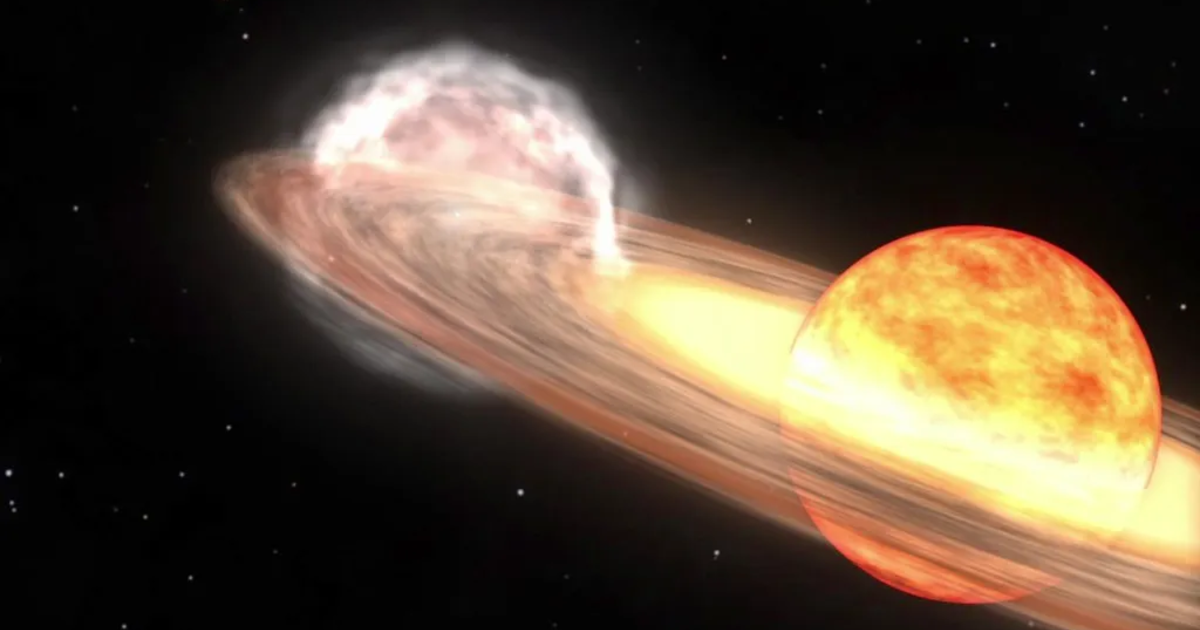

The technical term for the impending cosmic explosion is nova, which happens when a white dwarf lights up suddenly and often strikingly in the night sky. “White dwarf” is how astronomers describe a star at the end of its life cycle, after it has exhausted all of its nuclear fuel and only its core remains. As opposed to a supernova — another solar phenomenon visible from Earth, when a star effectively explodes — a nova instead refers to a dramatic ejection of material that a white dwarf has accumulated over time from a younger star in its close proximity.

“It’s a once-in-a-lifetime event that will create a lot of new astronomers out there, giving young people a cosmic event they can observe for themselves, ask their own questions, and collect their own data,” said Rebekah Hounsell, an assistant research scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center who specializes in nova events, in a statement. “It’ll fuel the next generation of scientists.”

Sometime between now and September, scientists expect that a nova in the Corona Borealis, or Northern Crown, of the Milky Way will send a flash so powerful into space that the naked eye can witness it, NASA announced recently. It will materialize in a dark spot in the constellation, where violent interactions between a white dwarf and a red giant are set to culminate in this massive blast.

NASA

A red giant is a dying star in the final phase of its life cycle, becoming increasingly turbulent as it expands and periodically expels material from its outer layers in intense episodes.

NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center

Known together as T Coronae Borealis, also named the “Blaze Star,” the white dwarf and red giant forecasted to create a nova this summer compose a binary star system in the Northern Crown, located around 3,000 light-years from Earth. The red giant in this pairing is constantly being stripped of hydrogen as it continues along its path toward total collapse, while the white dwarf nearby pulls that material into its own orbit, according to NASA. The hydrogen siphoned off of the red giant accumulates on the surface of the white dwarf over a number of decades, until the heat and pressure has built to such an extent that it prompts a full-blown thermonuclear explosion.

The blast, akin to a nuclear bomb in its appearance, rids the dead star of that excess material. The eruption will probably be visible on Earth for about one week before it disappears again, but both the white dwarf and red giant in the Blaze Star system will still be intact whenever it fades. At that point, the process of hydrogen buildup between the two stars restarts, and it will continue until the accumulation of material on the white dwarf reaches its threshold the next time and abruptly explodes.

Different binary systems like T Coronae Borealis move through this cycle at different speeds. A nova typically erupts out of the Blaze Star about every 80 years or so.

“There are a few recurrent novae with very short cycles, but typically, we don’t often see a repeated outburst in a human lifetime, and rarely one so relatively close to our own system,” Hounsell said. “It’s incredibly exciting to have this front-row seat.”

When the nova in T Coronae Borealis eventually occurs, it will be the first one out of that pairing witnessed from Earth since 1946, according to NASA. The agency advised hopeful stargazers to look for the Northern Crown, which it describes as “a horseshoe-shaped curve of stars west of the Hercules constellation,” on clear nights. NASA also encouraged citizens to observe the phenomenon as best they can, even though its own scientists will study the nova at its peak and throughout its decline.

“But it’s equally critical to obtain data during the early rise to eruption,” said Hounsell, “so the data collected by those avid citizen scientists on the lookout now for the nova will contribute dramatically to our findings.”